On 15 September 2022, the European Commission published its proposal for a new regulation setting cybersecurity standard for products with ‘digital elements’, known as the proposed Cyber Resilience Act (CRA).[1] The proposal for a law on cybersecurity standards for products with digital elements strengthens cybersecurity rules to ensure more secure hardware and software products.

Legislative background

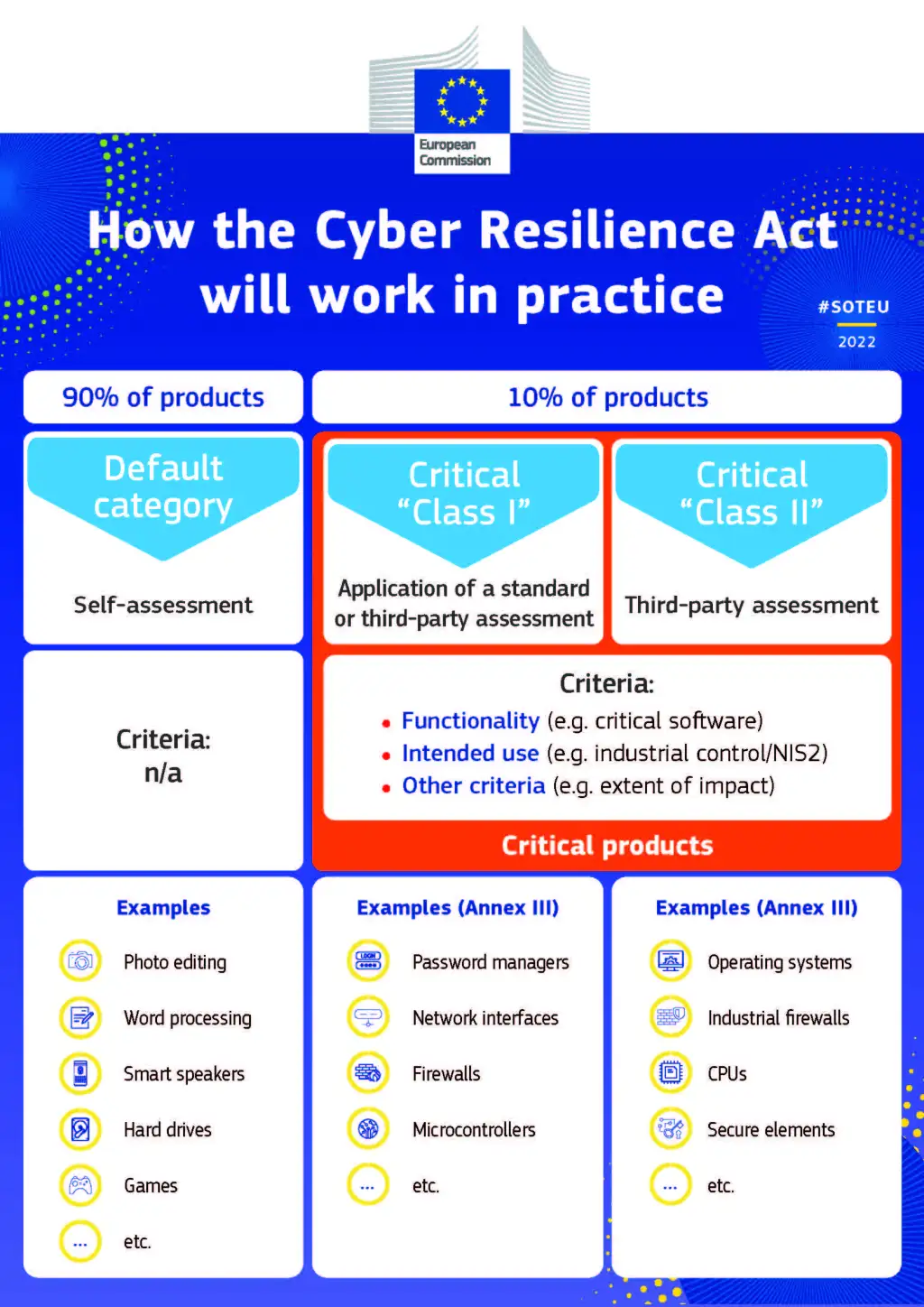

The proposed law included in the EU Cybersecurity Strategy for 2020,[2] would complement existing regulation, particularly the NIS2 Framework.[3] It would apply to any item that is directly or indirectly connected to another device or network, with some exceptions, such as open-source software or services that are already covered by existing regulations, such as medical devices, aircraft and automobiles. The NIS2 Directive requires Member States to identify critical and important companies and to impose a number of mandatory security and reporting obligations on the identified organisations. Compared to the previous NIS Directive adopted in 2016, the scope of the new legislation has been expanded to include several critical sectors, including energy, transport, banking, financial market infrastructure, health, drinking water, wastewater, digital infrastructure, public administration and space. DORA[4] is an additional cybersecurity law that can be seen as a subset of NIS2. It is primarily concerned with the security of ICT systems used by financial institutions, including banks, insurance companies and investment organisations. This legislation establishes a single framework to ensure the ‘digital resilience‘ of the system that facilitates monetary transactions across Europe and beyond. Finally, the Resilience of Key Entities Directive requires member states to develop a cybersecurity policy that identifies critical infrastructure.

These are far-reaching regulations for European device manufacturers. But as many in the industry will tell you, they are also the bare minimum for today’s digital world. Many modern gadgets have a low level of cybersecurity, as evidenced by numerous vulnerabilities and inadequate and inconsistent deployment of security updates to fix them.

Manufacturer responsibilities

When placing PDEs (items with digital aspects) on the EU market, manufacturers are required to carry out a cybersecurity risk assessment that considers threats at different stages of a PDE’s life, ultimately ensuring that the security of the supply chain is maintained from start to finish.

A manufacturer whose PDE is used in a variety of settings may need to understand the different uses and risks depending on the end user – for example, a guest registration software package may be used in both a small-town sports centre and a large city hospital, but the sensitive nature of the hospital is likely to present additional risks.

Manufacturers are then required to provide the risk assessment and additional information, instructions and technical documentation.

End-users are likely to try to put pressure on manufacturers to provide as much information about hazards as possible, while manufacturers are likely to try to provide the bare minimum in order to regulate the flow of information and the customer’s access to information in the event of a future dispute.

In its current form, the CRA will require a manufacturer to notify ENISA (the European Union Agency for Cyber Security) within 24 hours of becoming aware of an exploited vulnerability in a PDE or an event affecting the cybersecurity of a PDE. This includes requirements for vendors to notify an organisation that holds a component in its PDE of any vulnerabilities and for users to be notified of any events. It is feasible for companies to adopt contractual terms that allocate responsibility for vulnerability notification, based on their position in the supply chain and their corresponding bargaining power.

Companies will need to be able to identify the different entities and regulators that need to be notified in the event of an incident or, more broadly, based on the end user and the industry in which they operate. This will result in a complex web of reporting requirements and contractual reporting clauses will need to be modified to reflect these considerations. Depending on the seriousness of the offence, the Act provides for fines of up to €15 million or 2.5% of global turnover.

The proposed legislation is, in my view, extremely ambitious and will herald a major change in commercial software development, not only for EU technology companies, but for any company wishing to sell products in the EU. By classifying operating systems and Internet technology as high-risk Class 2 digital devices, non-European manufacturers of mobile phone technologies, laptops, desktops and computer server systems, such as Apple, Google, Microsoft, Intel, Sony, Huawei, AMD, ARM and Cisco, would have to comply with the requirements of the legislation for the majority (if not all) of their products. So I find it astonishing that the corporate community as a whole has made so few public statements about the serious implications.

Future Considerations and Preparations

The current draft CRA is still at the proposal stage and it will be some time before it becomes law. There will undoubtedly be some changes, but the draft shows a clear direction for EU cyber resilience legislation.

Dealing with the contractual transfer of risk for these fines under the CRA, in the form of indemnities for losses and warranties related to a company’s processes for compliance with the CRA, will be a crucial aspect of future business negotiations.

Even more challenging will be the ongoing monitoring of vulnerabilities in PDEs in the marketplace, especially as product lifecycles are extended over several years.

Companies will need additional monitoring resources, and those without these skills may need to outsource this task, requiring new service agreements and contractual risk allocations depending on which side of the PDE they are dealing with.

Many of the basic cybersecurity criteria are just a reflection of best practice, so many companies will not need to make a significant effort in this area. The complicated aspect is determining what type of conformity assessment products may be required and the creation/updating of a plethora of rules, procedures and other documents mandated by the CRA. The reporting requirements of the CRA will be in addition to the reporting requirements currently imposed by the Data Protection Act, the NIS Directive and other sector-specific regulations. Reporting requirements imposed on distributors and importers may also create tensions in the supply chain and during contract negotiations, as manufacturers will undoubtedly be concerned about distributors and importers informing market surveillance authorities of potential vulnerabilities in their products.

References

- https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/cyber-resilience-act ↑

- https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/eus-cybersecurity-strategy-digital-decade-0 ↑

- https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/nis2-directive ↑

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0595 ↑