Data is one of the main focuses of the European institutions, which aim to create an environment that encourages the use of data while ensuring an acceptable level of data protection. Data is the driving force behind today’s digital transformation.

The European Commission launched the proposed Data Act on 23 February 2022[1], as part of the implementation of the European Data Strategy 2020 and as a complement to the Data Governance Act (Regulation No 868/2022 of 30 May 2022)[2]. The proposed Data Act is currently in its final stages. In fact, the representatives of the Member States (Coreper) have reached an agreement that will allow the Council to start discussions with the European Parliament on the Commission’s legislative proposal, thus completing the process. The GDPR[3] (and similar legislation such as the Law Enforcement Directive[4] and the Digital Markets Act[5]) introduced a strict duality between personal and non-personal data, both of which represent a new generation of “data regulations” that will be abolished.

Aims of the proposal

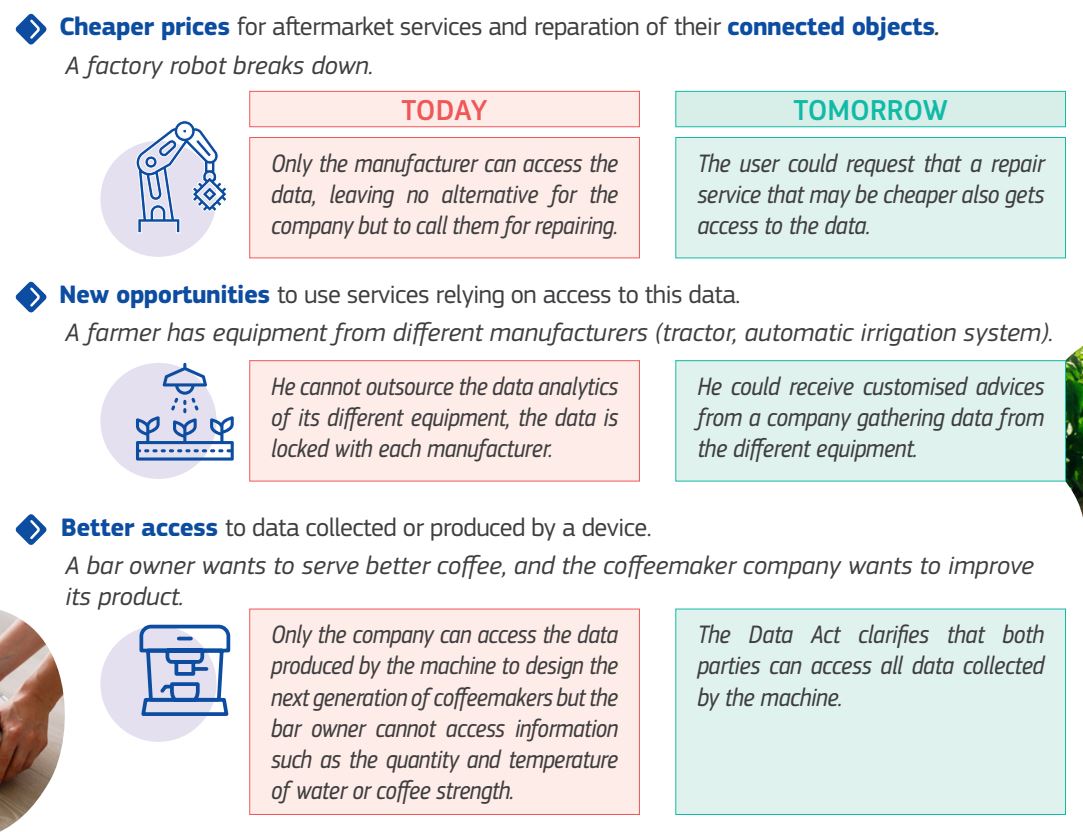

The proposed Data Act aims to remove barriers to data access for both consumers and businesses by establishing a single set of rules at EU level. To achieve this, the proposed Regulation creates standard guidelines to control the sharing of data generated by the use of connected goods or services (such as the Internet of Things, industrial machines), to ensure fairness in contracts, and to allow public authorities to use data held by companies in cases of exceptional need (e.g. public emergency). In addition, it establishes safeguards against unauthorised international data transfers by cloud service providers and new standards to facilitate the transition between cloud service providers and other data processing services.

In particular, the proposal in Chapter II regulates business-to-business and business-to-consumer data sharing by requiring that it be designed and produced in such a way that the data produced is readily and securely available (and, where appropriate, directly accessible). This obligation relates to the requirement that, prior to the conclusion of a contract for the purchase, rental or leasing of a good or related service, the user must be provided with a range of information in a clear and comprehensible manner, including, where relevant, details of the means by which the user can request that the data be disclosed to third parties. Article 4, which inter alia requires the data controller to make the data produced available to the user in a timely manner and free of charge (and, where applicable, on an ongoing basis and in real time) and makes the use of the user’s data by the data controller subject to the prior conclusion of a contractual agreement with the user, explicitly denies users the right to access and use the data generated by the use of related products or services.

On the one hand, there is ample room for the right to share data with third parties (art. 5), with specific restrictions for the providers of the basic platform services, designated as gatekeepers under the DMA, in order to avoid the risk of conditioning or modifying the user’s preferences, and on the other hand, for the obligations of third parties who receive data at your request, called upon to process them only for the purposes and under the conditions agreed with the user, and to delete the data when they are no longer needed. In addition, it’s against the law to condition or manipulate the user’s autonomy, to use the data for profiling natural persons, to disclose the information to third parties (unless this is necessary to provide the service to the user), to disclose the information to a company providing basic platform services for which one or more of these have been designated as gatekeeper, to use the information to create a product that competes with the one from which the data consulted originated (and there’s also a clause that says you can’t use the information to create a product that competes with the one from which the data consulted originated), to use the information to create a product that competes with the one from which the data consulted originated (and there’s also a clause that says you can’t create a product that competes with the one from which the data consulted originated).

Instead, Chapter V creates a single framework for the use of data held by companies by public sector organisations, institutions, agencies and bodies of the Union in circumstances where there is a particular need. Such a situation is deemed to exist in particular where the requested data are necessary to respond to, prevent or assist in the continuation of a public emergency (where the request is limited in time and scope) and for the performance of a specific task in the public interest which cannot otherwise be accomplished, provided that the requesting authority has not been able to obtain such data by other means, including by purchasing them on the market. Without limiting the situations in which the recipient may refuse or request a modification of the request, the data subject shall be required to provide feedback without undue delay in response to a request made pursuant to this Chapter, the details of which are set out in the same Regulation.

No payment shall be made for such hypotheses and any reimbursement shall not exceed the technical and administrative costs incurred in responding to the request. In all other cases, a public sector organisation or an institution, agency or body of the Union may communicate the data it has received to individuals or groups for the purpose of research or analysis compatible with the reason for which the information was requested, or to national statistical institutes and Eurostat for the purpose of compiling official statistics.

The Data Act and GDPR

The Data Bill aims to complement the GDPR and the Data Governance Act’s framework on international data flows by preventing the unauthorised transfer of, or access to, non-personal data by third countries.

The new rules aim to protect commercially sensitive data as trade secrets and data subject to intellectual property rights or confidentiality obligations under European law, in response to growing concerns about industrial espionage, intellectual property theft and unauthorised access to information by foreign authorities. A number of procedures have been put in place to ensure that the level of protection afforded by the European legal framework is maintained when non-personal data is transferred outside the EU.

Providers of data processing services are required to take all practical organisational, legal and technical precautions for these purposes to prevent international transfers of non-personal data held in the EU or government access to such data that would be contrary to EU or national law (e.g. commercially sensitive information, data that could affect security or defence interests).

Consider Article 27 of the proposal, which is in Chapter VII and focuses on international access and transfers of non-personal data, as an example of the difficulties that may arise from the interaction between the proposed Data Act and the GDPR. We are aware that the GDPR sets out precise guidelines for the transfer of personal data to other EU countries. Articles 44-50 of the GDPR set out clear requirements for the transfer of personal data outside the EU, including the need for international agreements or, alternatively, where the EU considers a third country to be ‘adequate’ for the protection of personal data or where other appropriate safeguards (such as binding corporate rules or standard data protection clauses) apply in that particular situation. On the other hand, there is no explicit guidance on the transfer of non-personal data outside the EU (other than sectoral or intellectual property rules).

The Data Act seems to have revolutionised this duality. Indeed, Article 27(1) requires providers of data processing services to take technical, legal and organisational measures to prevent the transfer of non-personal data in violation of EU or Member State law, adding a new layer of protection for international data access requests and transfers of non-personal data. In addition, Article 27(2) requires that any transfer of or request for access to data from a third country covered by the Data Act must be based on an active international agreement between the third country and the Union or the Member State concerned. In the absence of such an agreement, Article 27(3) provides that access or transfer may only take place after an assessment by the relevant competent bodies or authorities, which must determine whether the transfer or access request is reasonable. Conditions must be met before this decision can be challenged before a court or other authority. This becomes more problematic in the situation of mixed data sets, which are common in connected products such as smart home appliances. Would the status of the data transfer fall under the GDPR or the Data Act?

When reading these provisions, we can be confused as to whether they duplicate Articles 44-50 of the GDPR and use the same guiding principles, or whether they follow a different set of rules. What do these “legal and organisational measures” actually mean for the transfer of non-personal data? Can we take into account the GDPR’s protections for the transmission of personal data here, or are data controllers free to impose a lower threshold for non-personal data?

Furthermore, if based on an international agreement, court rulings and administrative decisions from third countries requiring the transfer of or access to non-personal data held in the EU will only be recognised or enforceable. Otherwise, certain strict conditions must be met for the transfer or access to take place, and only the minimum amount of data permitted may be transferred.

In this respect, the Draft Data Act has taken on board the statements of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) on the transfer of personal data in the Schrems II case[6], which called for a preliminary assessment of the legal and judicial systems and practices of third countries to determine whether such transfers comply with the requirements and safeguards of European law.

This would have significant theoretical and practical implications, as it would apply the strict data protection framework of the GDPR to all other categories of non-personal data. In the second situation, more information and clarifications are needed, as the application of protection mechanisms designed for personal data to non-personal data would fundamentally change the state of data protection as we currently know it.

Sanctions and enforcement

The national authority responsible for implementation and enforcement, as well as the framework for sanctions for breaches of the Regulation, must be designated by the Member States. As sanctions may vary from one country to another, even if the Data Act were a directly applicable regulation, this transposition option could prevent harmonisation in the area of sanctions. On the other hand, those who consider that their rights under the Data Act have been infringed can lodge complaints with the competent authorities.

The broad application of the law, which covers different types of connected entities performing different functions and collecting different types of data for different purposes, makes it difficult to monitor. Recognising this fact, Article 31(1) and (2) states that the enforcement of the Data Protection Act, as far as the protection of personal data is concerned, shall be the responsibility of the Data Protection Authority (DPA) of each Member State. At the same time, Article 31 states that different authorities, such as consumer protection authorities, may be qualified to enforce the law in different Member States, and that an independent competent coordinating authority, designated by each Member State, will be responsible for the overall application and enforcement of the Data Act. As a result, there are still many questions about how different authorities will work together, as mixed datasets of linked items and the interconnectedness of personal data may limit the scope of authority of DPAs or result in significant overlap. This further complicates enforcement from a user perspective, as data subjects may be confused and left in limbo when it comes to making a complaint under many overlapping regimes.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the Regulations will have extraterritorial effect and are likely to be adopted as international norms outside the EU, as was the case with the GDPR and is likely to be the case with the forthcoming AI Act, Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, increasing the EU’s influence globally.

Criticism

Criticism to the Data Act arose promptly in 2022[7] and continued to gather support from the Western tech corporate world. The main points of criticism are synthetised in the joint letter – following a joint statement of February 2023[8] – that a group of big tech sent yesterday to EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, antitrust chief Margrethe Vestager and industry chief Thierry Breton[9]. Signatories of the letter are – among others – the CEOs of Siemens, the German medical technology company Brainlab, the German software company Datev and the pressure group DigitalEurope.

Roland Busch, CEO Siemens AG stated[10]:

“Europe’s digital industry is a major driver of economic growth. We want to increase its competitiveness and continue to deliver prosperity. The EU Data Act should help us to achieve that: by avoiding legal uncertainty; by protecting sensitive data; by safeguarding trade secrets; and by advancing cybersecurity.”

Among the criticisms from the US, it states that the proposed law is too restrictive[11], while German companies argue that a provision requiring companies to share data with third parties to provide after-sales or other data-driven services could endanger trade secrets. The letter additionally called for safeguards to allow companies to refuse data-sharing requests in the event of trade secret, cybersecurity, health and safety risks, and asked that the scope of devices covered by the legislation not be extended.

Regarding the provision allowing customers to switch from one cloud provider to another, the companies argued that the legislation should preserve contractual freedom, allowing customers and providers to agree on the contracts best suited to each business case.

Christian Klein, CEO and Member of the Executive Board of SAP SE stated[12]:

“SAP welcomes the objectives of the EU Data Act to create a common EU regulatory framework for the data economy and to facilitate data sharing. Broader data usage not only enables productivity and growth but can also help fight climate change at scale. However, the Data Act should also preserve contractual freedom, allowing cloud providers and customers to agree on terms and conditions that reflect business needs. Fixed-term contracts should not be questioned by the Act as they have proven to be beneficial for both cloud providers and customers.”

Conclusion

The Data Act was adopted by the European Parliament in early March with 500 votes in favour, 23 against and 110 abstentions. Thanks to the agreement on the Council’s common position, the Swedish Presidency can now start trilogues on the final draft of the legislative proposal. This is a crucial component that will complete the picture painted by the Strategy, which began with the Data Governance Act, which established the structures and procedures for facilitating data, but still needs to clarify who can derive value from data and under what circumstances.

We are now at a critical juncture in the formulation of European digital policy, which has a difficult but essential task: to strike the right balance between the need to ensure effective and efficient protection and the need to enable access to and use of data.

References

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2022%3A68%3AFIN ↑

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32022R0868 ↑

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj ↑

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016L0680 ↑

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/1925 ↑

- https://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?num=C-311/18 ↑

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/tech-giants-to-be-forced-to-share-more-data-under-eu-proposal-11645618258 ↑

- https://digital-europe-website-v1.s3.fr-par.scw.cloud/uploads/2023/02/Data-Act-industry-joint-statement-1-February-2023.pdf ↑

- https://fortune.com/2023/05/08/european-tech-leaders-are-speaking-out-against-the-new-eu-data-act/ ↑

- https://www.digitaleurope.org/news/ceos-call-for-urgent-rethink-on-data-act/ ↑

- https://www.reuters.com/technology/eu-lawmakers-body-agrees-safeguards-against-illegal-data-transfers-2023-02-09/ ↑

- https://www.digitaleurope.org/news/ceos-call-for-urgent-rethink-on-data-act/ ↑